Political & Religious Persecution

Wu worried about his country’s evolving role and social turbulence and decided to write to China’s leaders to express his concerns. Despite the risk he knew it would entail, Wu's aspiration to serve this country and the people of China impelled him to send a letter to the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. He wished could help his country resolve some of its difficulties as it moved into the new millennium.

Letter of November 20 , 1998

On November 20, 1998, Wu sent a letter titled “Suggestions to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and State Council.” In the letter, Wu suggested reforms for the transformation of China's social system. Wu warned of turbulence brewing among the people of China and described the measure he considered essential to effecting needed change. (Chinese Version Download)(English Version Download)

Among those reforms advanced, Wu called for full transparency of all affairs of government and for the creation of a governmental oversight body, with the power to review the actions of communist party officials at all levels and to impeach those individuals found to have acted improperly, making national and local government transparent and accountable to the people, and developing a democratic constitutional system for China.

He concluded with a prescient observation: “Throughout Chinese history, most civilians who commented on politics did not have peaceful endings. Here I express my feelings to end this letter by quoting a verse from a famous Chinese poem: ‘Fear not death, my body and mind are embedded in the mountains and rivers’.”

Although Wu intended the letter to be part of a constructive dialogue with the ruling party and that it would lead to desired reforms, the action was taken to be political dissidence, resulting in Wu's name being placed among those government regarded as a threat to the nation's security. Immediately following the transmittal of the letter, Wu's involvement with, and the activities of, the Huazang Consultation Center came under that constant scrutiny of the China National Security Department.

Letter of July 9, 1999

On July 9, 1999, Wu sent a letter to Chinese President Jiang Zemin, Prime Minister Zhu Rongji, and the Chinese Community Party. Already under substantial pressure from the Chinese Communist, he began the letter by stating, “I might be in jail before I can finish and mail this letter . . . I am not concerned for my own safety, but for the fate of our great China and the well-being of her people.” (Chinese Version Download) (English Version Download)

In this letter, Wu provided further background on his work and Buddhist teachings. He described his experience with the Chinese Qigong Society, which he viewed as having been corrupted, and his reasons for founding the China Life Science Society. He also explained his efforts to teach Huazang Mind Dharma in higher education institutions, his development of his theory of “Harmonious Unification,” and his exhortations to people to bring prosperity to the nation by perfecting their conduct.

Wu indicated he understood that the “bureaucratic ideology that dominates governmental action is China is causing more and more discontent among the people, as citizens are denied the right to be heard, and inevitably will lead to conflict between the people and government.” He further stated that “if an appropriate solution is not found, one day the government will collapse. As the Chinese proverb warns: ‘Miles of levees can be destroyed by a small hole’.” He added that “forced and formalized political indoctrination, because of the discontent among the people, is not effective and may be having an adverse impact.”

After submitting his letter the prior year, Wu explained that his Beijing Huazang Consultation Center immediately began being monitored by the National Security and Public Security departments. Numerous individuals affiliated with the Center were also detained and questioned thoroughly about its operations and ultimate goal. He said that given the warnings from these government agencies, he decided to establish a company called Huazang Enterprises, Inc., whose purpose was to be devoted to supporting the poor in remote depressed areas and to generate employment for the unemployed. Despite having been as transparent as possible about his goals, Wu noted that his local Public Security Department had shut the company down and questioned his management committee in June, 1999, later charging them with “illegal fundraising and stock issuance.” Despite having the requisite government approvals, the company’s accounts, with investments from more than 1,000 families totaling 19 million yuan, were frozen.

Wu concluded by making clear that as far as he was aware, everything had been done in accordance with Chinese law, and he believed that the Chinese government’s actions against him were unjust and unlawful.

Arrest, Investigation, and Indictment

On July 31, 1999, Wu was officially taken into custody by the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau and arrested.

Ironically, after Wu was arrested, newspapers reported the approval of Huazang Enterprise Company by the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau, heralding it as the first private joint-stock company initiated by private citizens to support the poor in remote areas and create jobs. A source from the Beijing Municipal Commission for Restructuring Economic Systems noted, “This form of company is new to Beijing and rare even in the rest of the country. It is an important supplement to the non-state- owned part of China’s economic system.” Apparently, these state-run news outlets hadn’t been informed the Chinese government was in the process of shutting down this innovative approach to poverty alleviation and of prosecuting its founders.

On September 10, after some 44 days in custody, Wu was notified in his arrest warrant that he was suspected of “being involved in illegally collecting money from the populace.” This was later changed in August and September to “illegally raising funds,” and ultimately to the “issuance of unauthorized shares and performing illegal operations.” Over the course of the four months between his arrest and beginning of his trial, Wu was interrogated daily and subjected to severe and prolonged sleep deprivation. “I was not allowed to sleep any part of the day. This lasted for the first four months and I hardly had any appetite at all,” he recalled."I was not asked anything regarding Huazang’s so-called economic problems; rather the focus of the questions was on my background and the organization’s structure and personnel. I asked them,‘Why am I being held in custody? Have I committed any crimes?’ They answered ‘No’.”

Once the investigators tried to break Wu down spiritually, he refused to cooperate. He told them that they can write a statement and he will sign it. Suspicious, the police asked if he would seek to reverse this statement in court. He told them, “No.This is just a process. I have told you what I have to say. I don’t have anything to conceal. You don’t have to ask me, you can investigate yourselves.”

After signing the arrest warrant, Wu began negotiating with authorities. He said that if all the other Huazang personnel were released, he would cooperate with them. Wu explained that during the whole interrogation, he repeatedly said “I initiated the company, I signed the documents for fundraising, I appointed the personnel for the preparatory team, they were not responsible for any specific matters, and I am the only one who had control throughout the country.”

The Trial

Wu Zeheng and his colleagues’ trial began on November 2, 2000. As the court session opened, Wu recalled an extraordinary exchange with the Judge: “We were told your sentence must be over ten years.We can’t disobey.We decided to sentence you to eleven years, which can be regarded as over ten years’.”

Sentence

There was only one court session. The court later issued its verdict on December 20, 2000. The court explicitly acknowledged it had “refused to verify relevant evidence presented by their defendants’ counsel as they cannot confirm the facts in this case.”

Wu was convicted and sentenced to 11 years imprisonment for “illegally issuing stock” and “illegally operating a business.” In addition, he received two years deprivation of political rights and was fined 2.5 million yuan ($302,000). Based on his pre-trial detention, he was scheduled for release on July 30, 2010.

Appeal

On appeal to the Beijing Higher People’s Court, Wu Zeheng’s lawyer made a range of arguments, but the appeal was swiftly rejected on November 2,2001.

Prison and Torture (2001-2010)

How can anyone withstand one year of prison abuse, mistreatment and torture? Yet Wu Zeheng withstood not just one year but eleven of increasingly severe abuses and torture. Not only did he withstand it, he fought back and remained unbroken in spirit. This section shows in detail what Wu went through.

Deportation Center (2001)

During his first week of indoctrination, Wu’s head was shaved, he was forced to wear a prison uniform, and he was beaten by some of his fellow prisoners as instructed by policemen. There were 27 prisoners in one cell, with only three beds. New prisoners were put to work packing disposable chopsticks. Each prisoner had to pack 2,500 pairs of disposable chopsticks before being allowed to rest. Prisoners were forced to remain in a squatting position. Water was provided twice a day, a half cup at a time. The daily meal was a steamed bun with preserved Sichuan pickles. After just a week in the deportation center, Wu had already concluded, “To tell you the truth, a person who lives a hard life, has illness or even faces death, experiences nothing compared to the most unbearable spiritual torture and humiliation.”

Lian-ping Prison (2001-2002)

After the first week at the Deportation Center, Wu was transferred to Lian-ping Prison for a month-and-a-half of prison indoctrination. The purpose of the experience is to transform a person into a real prisoner by breaking their mind and body. Prisoners must learn the rules and be absolutely compliant with demands of prison guards. Physical and mental abuse was constant.

After completing his indoctrination, Wu decided to test the Chinese government. Interrogators had made clear he wasn’t imprisoned for his so-called economic crimes, but they never acknowledged he was being persecuted for his religious practice. Having heard from his students there were a number of people wanting to become Buddhist, he wrote letters to his students advising how to arrange for a Buddhist conversion ceremony to happen at Zou Quan Temple. The ceremony took place on April 8, 2002, and Wu made his involvement known to authorities. On May 17, he was transferred to Huai-ji Prison.

Huai-ji Prison - Unit IV (2002-2005)

Upon arriving at the new prison in Guangdong Province, which houses only the most severe criminal offenders, Wu was placed in solitary confinement in a very small room for eight days with only a flush toilet and flea-infested wooden bed without a blanket or pillow. When he fell asleep, he was quickly awakened by the bites of large rats, which were unafraid of people. At mealtime, the small door to his cell was opened and Wu was fed a dish of spoiled grain. Wu asked the guards why he had been placed in solitary confinement and they indicated they had no idea – and they also had no idea when he would be let out.

After eight days, Wu was transferred to Unit IV, where he was placed in Cell Six of the West Wing. A short time later, a prisoner named Zheng Shui-you who had tuberculosis was transferred to Wu’s cell. Wu recalled: “They discharged Zheng from the isolation ward of the hospital and placed him in the same cell with me, sharing the same space and using the same necessities. Within a month, I was infected. At the end of the year, the Preventative Treatment Center of Contagious Disease found more than 100 prisoners were infected with tuberculosis. Everyone that was infected, except me, was isolated and provided treatment. Instead, I continued to be forced to work fourteen hours physical labor and to perform three hours of study.”

Eventually Wu was provided treatment – but only for a month – ensuring a later relapse. When Wu was reassigned to work, he was placed in the area of the prison that manufactured toys. The toys manufactured at Huai-ji prison were being produced for a major international fast-food chain. Unlike the other prisoners who were given a cushion, Wu was forced to sit on a hard bench for 14 hours a day. From the first day, his bottom became abraded and got worse with each passing day, soon becoming infected and oozed pus and blood. Each day, after completing a duty shift, his pants were stuck to his wounds. After his eleventh day since being diagnosed with tuberculosis, Wu’s fever had risen to 104.4 degrees Fahrenheit (41.7 degrees Celsius). While at his station, Wu fainted and collapsed. To his astonishment, prison officials punished him for “sleeping without authorization.”

In the meantime, requests for a cushion and medicine for his buttocks were refused for more than 40 days. Wu recalled, “When I tried to shower at night, it was horrible. With my broken flesh melded to my pants, each time I needed to remove them, a big piece of flesh was torn off, causing excruciating pain.” His weight dropped from 85 kg (187 lbs) at Lian-Ping Prison to 55 kg (121 pounds) at Huai-ji Prison.

The work schedule was unbearable. The work day began at 5:00 am when prisoners were awakened and given only 10 minutes to get ready for work. Breakfast was served at 5:30 and by 5:45 am prisoners were at their work stations until 12:30 pm. Prisoners were allowed one hour for lunch and then they returned to work from 1:30 pm until 7:00 pm. Dinner ended at 8:00 pm and the final shift ended at 11:30 pm. Prisoners who failed to meet 70% of their quota, arbitrarily determined by the guards, were required to attend a “study session.” At these sessions, they were forced to undergo the “golden pheasant” – standing at attention in the prison yard. When the guard shouted “one,” the prisoner had to bend his knee and lift one foot off the ground. He was not allowed to put his foot down until the guard yelled “two” – but that usually took 10-20 minutes. These sessions usually lasted 40 minutes after the ending of the final shift. Usually prisoners were given a training period of a month-and-a-half before being assigned the highest quota. Wu was immediately given the highest quota – but upon complaining about the study session, this requirement was lifted for him.

Fellow prisoners were assigned to watch Wu at all times and were encouraged to do whatever they wanted to make his life miserable by being promised reductions of their prison sentences. Thus, Wu would regularly find his personal effects missing, be bumped by prisoners walking by, and have hot water spilled on him. The more the prisoners bullied Wu, the more they were rewarded. Wu only learned later why this was happening to him.

As if life weren’t miserable enough, the prison was without water intermittently for seven months a year regardless of summer and winter. Given work involving the manufacture of toys, prisoners desperately needed showers because they were covered in dust and very smelly. When there were water shortages, only one area of the prison received water, and prisoners would have to wait long periods to shower. In the summers, this was bearable, but in the winters the weather was cloudy, drizzling, cold, and wet. To make things worse, the water supplied to the prison was drawn from a spring flowing from high up in the mountains and was 20 degrees F (minus 7 degrees C). After a brief shower, prisoners came out shivering. By the time a prisoner felt himself becoming warm, it was time to get up again.

At a certain point, Wu informed prison officials that their manufacture of prison-labor products for export was illegal. In response, he was told that no one at the prison was aware of the law and that he was betraying his country by “divulging state secrets.” The next day Wu was transferred to a different part of the manufacturing operation, with much more difficult work on small toys, requiring use of pliers and sewing machines together, which resulted in frequent injuries. In this new area, prisoners who failed to meet their quotas were thrown in a pool and electrified, though Wu stood up to prison guards demanding they stop this method of torture. For standing up for another prisoner who was being beaten, Wu was denied an entrée with his meal for seven months.

If anyone talked to him, that prisoner would get an additional six months imprisonment. When Wu realized that speaking to other prisoners resulted in only those prisoners’being punished and not Wu himself, he decided not to speak to others. Once he understood this reality, Wu isolated himself from other prisoners to spare them further punishment. All day every day, with the exception of saying his prison number in response to a prison instructor, he had not uttered another word for more than three years.

Eventually an incident changed how the prison guards managed Wu. The night before a mid-moon festival in September, 2003, a few prisoners beat another prisoner to death in Unit VI. Other prisoners were informed of this development a short time later. Those prisoners who were involved were put in confinement and later transferred to a different part of the prison. Wu learned that one of the persons who had beaten the prisoner to death was an acquaintance of his whom he later saw getting some hot water. He heard directly what had happened in the beating death but his acquaintance told Wu he wasn’t concerned about being punished because if the two prisoners most responsible were executed and the two others who were also involved (which included him) were given extended sentences, then the warden would be relieved of his duty. At the end of that year, the warden announced to the prisoners that the death earlier in the year was the result of a heart attack.

During 2004, Wu out-performed his required work quota every month which should have resulted in a reduction of his sentence. According to Chinese prison regulations, prisoners who finished their yearly work quota in ten months were assessed as an “outstanding performer” and given a year-and-a-half sentence reduction. Although Wu achieved this goal, he was told that his application for the sentence reduction had been disqualified.

By this time no one was allowed to visit him, and he had to live on 10-20 yuan ($1.21 – 2.41) every month. This money could only buy toilet tissue and washing powder. Wu could not even use toothpaste for nearly nine months because he couldn’t afford it.

On December 5, 2004, Wu sent a detailed complaint to the National People’s Congress to draw attention to the horrific prison conditions that he and others lived under. In this letter, he detailed the humiliation that he had been subjected to by prison officials. He was particularly aggrieved by a repeated focus on his religious activities when his conviction and sentencing allegedly had nothing to do with his being a Buddhist. For example, he complained about the failure of prison authorities to grant a sentence reduction to him shortly after his arrival in Huai-ji Prison. He reported that the Deputy Warden and another official had told him his eligibility for the six-month reduction had been withdrawn because he had “been persuading other inmates to participate in religious activities while serving a sentence in Lian-ping prison, which is an illegal act.” (Chinese Version Download)(English Version Download)

On December 5, 2004, Wu sent a detailed complaint to the National People’s Congress to draw attention to the horrific prison conditions that he and others lived under. In this letter, he detailed the humiliation that he had been subjected to by prison officials. He was particularly aggrieved by a repeated focus on his religious activities when his conviction and sentencing allegedly had nothing to do with his being a Buddhist. For example, he complained about the failure of prison authorities to grant a sentence reduction to him shortly after his arrival in Huai-ji Prison. He reported that the Deputy Warden and another official had told him his eligibility for the six-month reduction had been withdrawn because he had “been persuading other inmates to participate in religious activities while serving a sentence in Lian-ping prison, which is an illegal act.” (Chinese Version Download)(English Version Download)

In mid-May 2004, the Deputy Warden and an investigator told Wu, “Because your Huazang Mind Dharma is an illegal organization and a menace to society, you must write a report setting forth your activities and thoughts regarding ‘Huazang Gong’ to be used as a measurement of your rehabilitation progress.” Wu further reported to the National People’s Congress that he sent a letter to the Deputy Warden stating he had been imprisoned for economic crimes and not in relation to the activities of Huazang Mind Dharma itself and that he would only accept punishment for crimes for which he was convicted, but not punitive measures unrelated to those crimes which are themselves illegal. Wu was told that unless he submitted monthly reports on Huazang Mind Dharma, regardless of how well-behaved he had been, he would not receive any administrative rewards, including sentence reductions. He learned later this was the basis for the prison authorities refusing to grant him the reduction for having met his quota for the year early.

Ultimately, Wu should have received a total of five-year reduction in his sentence for having met his quotas in 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009, but he only received a total of five months. Wu concluded his letter to the National People’s Congress by questioning how he came to be determined to be a security threat without any due process of law.

In early 2005, Wu became the first prisoner in China to ever try and file a claim against his prison and Chinese government officials. He later learned that despite prison regulations requiring the lawsuit to be submitted, the prison officials had ensured it disappeared. He subsequently filed an administrative claim before the Huai-ji County People’s Court for refusing to reduce his prison sentence after he regularly met his work quotas and for its having refused to return personal items to him that had been taken when he entered the prison. A short time later, the claim was put on the record and then made public by supporters on the Internet. “They had to announce and register my case,” recalled Wu. The costs for accepting and hearing the case were 100yuan ($12.08) and deducted from Wu’s account, which left him with nothing. A short time later, two officers from the Department of Justice in Guangdong Province came to see Wu. At first, he thought they might be willing to hear his case, but they wouldn’t listen to what he said. They even showed him what they intended to report, which didn’t include Wu’s remarks. Despite prison regulations requiring the suit to be decided in six months, it took nine months for the claim to be denied.

.

Within five days Wu made an appeal to Huai-ji Intermediate Court. Despite the clear violation of Chinese prison regulations, the appeals court affirmed the original verdict on jurisdictional grounds, claiming it didn’t have the authority to hear the case. Not only were his claims for reduction in time dismissed, but the court also allowed prison officials to fail to produce a list of personal belongings that had been seized from Wu over his incarceration, which included over 40,000yuan ($4,800) of personal belongings. In response to these judgments, Wu recalled, “All my appeals were invalid . . . because it is impossible to obtain justice in China. The authorities themselves flagrantly violated the law. They made the law to control the common people at their will and they were above and beyond the reach of the law. So it is meaningless to prosecute them in court. I had to try to use another strategy.”

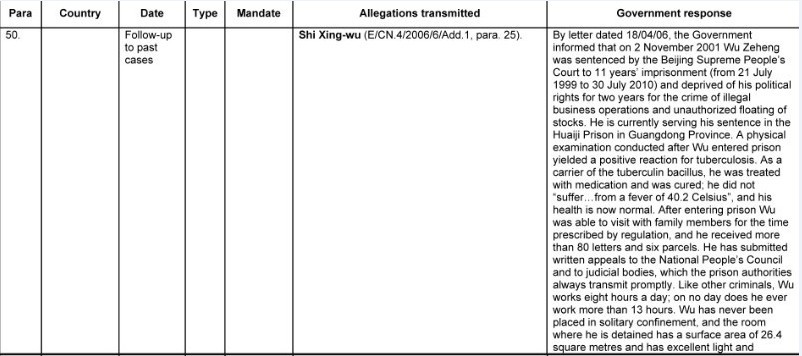

On June 5, 2005, an urgent action appeal was filed with the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture regarding Wu’s ongoing torture. In the appeal, she detailed his mistreatment at the hands of Chinese authorities. In response to these assertions, the Chinese government replied to the Special Rapporteur on April 18, 2006, denying infecting Wu with tuberculosis, his high fever, his incommunicado detention, his period of solitary confinement, and that he regularly works more than eight hours a day. The Chinese government assured the Special Rapporteur, “Wu’s legitimate rights and interests are guaranteed in accordance with law.”

Wu’s Rebuttal

From the outset of Wu’s imprisonment, Chinese authorities were intent on seeing his life ended. They saw Wu as a threat to its hold on power due to his intelligence, his considerable talents at communication, and, most significantly, to his stature as a religious leader having millions of followers. However, for that reason, to avoid igniting a revolt, they knew Wu’s death had to appear to be the result of natural causes. To that end, they created circumstances that to varying degrees inflicted harms that threatened Wu’s life. They intentionally exposed Wu to tuberculosis and denied him essential medical treatment; they forced Wu to work 14 to 16-hour days, even when suffering from the effects of severe injury or illness; and they incited Wu’s fellow prisoners to torment and provoke him by offering them early release and other incentives.

Of the various attacks on Wu’s life, the deliberate effort to cause Wu to contract tuberculosis is the most flagrant. Within days of Wu’s arrival at Huai-ji Prison, administrators intentionally placed in Wu’s cell a prisoner from the isolation ward who was infected with tuberculosis and extremely contagious. Wu had no prior history of previous exposure to the disease. Less than one month later, Wu and many others within his Unit were suffering from the effects of tuberculosis, including spitting blood and suffering from high fevers. Everyone except Wu was isolated and allowed rest and proper treatment. For Wu, however, work on the production line continued, even when Wu’s fever reached 40.2 Celsius and he collapsed into a coma. Despite efforts by the prison doctor to intercede on Wu’s behalf, Wu never received the standard treatment regimen.

Aside from doing what they could to hasten Wu’s death from “natural causes”, government officials subjected Wu to the same or similar harsh treatments and conditions as the other prisoners. In Wu’s case, their intent was to make his life as miserable as possible, so that if he managed to survive his spirit would be broken and he would not dare voice objection to government rule again. For eight days, Wu was locked in solitary confinement, a pitch-black cell crawling with large rats that would bite Wu’s body as he slept. The food rations Wu and the other prisoners received were spoiled rice and grain that when cooked tasted sour and stank. Although it had rotted to the point that it was unfit for human consumption, after a while, the prisoners forced themselves to eat it.

Contact with the outside world was controlled strictly. For this reason, it was almost impossible for Wu to convey details regarding the abuses he suffered, whether to his family, friends, and followers or to the other government agencies. At great risk to his own safety, Wu managed to pass along sensitive accounts regarding how he and his fellow inmates were being treated. One letter, dated Dec 5th, 2004, directed to the National People’s Committee, revealed glimpses of the harshness of life within the prison. As with all documents of similar import, the letter reached outside the walls of the prison because Wu was intent on exposing the atrocities being committed and the inhuman conditions within China’s prison at Huai-ji.

Insofar as the Chinese government’s contention that China has no one at any of its prisons by the name Shi Xingwu, the response is evasive and disingenuous. Wu was a prominent Buddhist leader, known to Chinese authorities well before his 1999 arrest, both by his family name, Wu Zeheng, and by his Dharma name, Zen Master Shi Xingwu. The primary reason the government In September 2005, he learned the Huai-ji County People’s Court had issued a ruling finding the case inadmissible on jurisdictional grounds ruling that Wu complained of violations of prison regulations, which were outside the scope of review of the People’s Court. He filed an appeal within days to the Guangdong Zhao-qing Intermediate People’s Court.

The Court later rejected the appeal and upheld the original ruling finding his treatment constituted the prison’s management of its prison population and did not constitute administrative actions within the jurisdiction of the People’s Court.

Wu also decided to make his complaints public, filing a claim with the Department of Justice and Supervision Administration Bureau about his mistreatment and ensuring it was posted on the Internet. Four personnel were punished for this. Not long after the news was transferred to the Internet, Wu was transferred to Unit VII on December 28, 2005.

Huai-ji Prison - Unit VII (2005-2010)

After being transferred to unit VII to punish Wu further, he was held incommunicado and denied access to the outside world. Those two years were the hardest time for him. Once transferred, he was under the most restricted control. He was denied all personal effects, including toilet paper, sufficient clothing, or even a quilt for when he was very cold. Anywhere he went, even to the toilet, he was followed by a prison guard. Wu had nothing and everything was terrible. Wu had to keep running in the corridor to keep warm. At the same time, he was tailed by two people.

Wu’s health deteriorated after his arrival in Unit VII. This was both because of the harsh conditions and ongoing torture. He grew quite ill on two occasions during his first year in Unit VII. On three occasions, herbal medicine he had been prescribed disappeared in the midst of treatment. So he would have to restart the treatment each time. Wu realized this was all intentional conduct on the part of prison officials. Eventually, the Deputy Warden was replaced. He re-started his treatment but on the last day, his medicine disappeared again. He found them thrown in the toilet. As he reflected on this especially difficult time, he noted: “They hoped that I would die from illness or any abnormal disease in prison, they wanted to increase my sentence, or force me to become mad one day. But they didn’t achieve their aim.”

As the repression increased, Wu’s resilience increased. The prison officials changed their tactics and he adjusted to the new repression. Each time he rebounded a few prison officials would be punished and a new group of them would try a different way to break him. During 2007, prison officials had given up and looked to make a deal with Wu. They told him they could get him what he wanted except guns or drugs if he would stop bothering them. Wu replied by stating they would have to correct the wrongs they had inflicted upon him and apologize for what they had done. He said he would not stop defending his own rights if his rights continued to be violated. He said if the Chinese government wouldn’t let him proceed in China, he would bring his case to the United Nations. The prison officials continued to pursue reconciliation with him. They offered him early release if he “gave up” – but Wu replied that he had already been in prison for eight years and was prepared to serve the rest. Wu recalled “On the one hand, I would not and could not give in. On the other hand, I felt so lonely and so aggrieved now and then. So they absolutely didn’t expect I could survive. They can break me down physically, but not spiritually. It was not one day. It was eleven years ! ”

Despite the hardships, physical disease, and ailments, Wu managed to survive and come stronger spiritually.

Release (February 28, 2010)

On February 28, 2010, after enduring 11 years of terrible mistreatment, Wu was released from prison. A month later, on March 24, Wu posted his first open letter to the public. It was directed to those people who continued to be suspicious of, oppress, or humiliate him, and expressed his desire to engage in dialogue based on equality, fair-mindedness, and mutual understanding so that he may be accorded basic legal rights and dignity under law. He noted the ongoing repression: “Even though I have been released from prison, I frequently suffer the ‘care and attention’ from authorities; I am unable to enjoy the legal freedoms and rights to which every citizen is entitled; and I am unable to have a normal life.”

He further explained that while he expected a bright future for China, he was deeply concerned about its “inferior and depraved character.” Wu said, “I eagerly look forward to the day, under the auspices and direction of the Chinese Communist Party, when we have democracy, freedom, equality, and a harmonious and prosperous society for people.”